Dangerous Watercolors: Nolde and Nickson

Evening Landscape North Frisia, date unknown

Emil Nolde

Nolde Stiftung Seebüll, Germany

Emil Nolde (1867-1956)

Although he joined the Nazi party in the early ’30s, Emil Nolde’s paintings were confiscated from the museums and his work was slandered as Degenerate Art.

From 1941 on, he was prohibited from making art at all. Nolde, who was then in his seventies, secretly continued to paint…dangerous paintings, indeed.

He turned to watercolor for fear that even the smell of oil paints might give away his covert paintings. He lent many of his works to friends for safekeeping, in order to protect himself and his art from Gestapo raids. Others he hid in the floorboards of his house.

Nolde called these small watercolor sketches, the size of postcards, “my unpainted pictures,”… “unpainted” in the sense that they did not officially exist and were not supposed to exist.

Seventy years later, these gorgeous, diverse, and quietly moving “unpainted pictures” continue to be nothing short of brilliant.

_______________

Sarageto VII, 2008

Graham Nickson

Graham Nickson (born 1946)

Twenty-six years old and a new recipient of the prestigious Prix de Rome, Graham Nickson arrived in Italy to train at the distinguished British School at Rome.

Graham Nickson: “A terrible thing happened when I first got to Rome, and it was probably one of the most important events in my life.

The year was 1972 and I arrived in Rome in the middle of a thunderstorm. It was raining so badly that it was impossible to find a hotel. I had arrived way before the time I could take over my studio.

I had brought with me a portfolio of about two hundred of my best gouaches and drawings. I left the portfolio in the car, because it was raining so hard. Twenty minutes later, when the rain had subsided slightly I found that somebody had put a brick through the window and stolen the lot. There I was, with all my history gone.

After simmering down a couple of days, I went up on the roof of the Academy. I was looking at this dramatic sky, and it occurred to me that the most dangerous thing would be to paint the sunset, and then the sunrise because it’s so clichéd, so hackneyed. Even at its best, it had already been done so well by Turner, Nolde, and other artists.

Before I knew it I had painted every dawn and sunset for two years.”

Graham Nickson is the Dean of the New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture, New York City. The Metropolitan Museum of Art holds eleven of Nickson’s works in their permanent collection.

Nickson continues to paint evening and morning skies on a regular basis.

Graham Nickson has an exhibition through May 22, 2015, at the Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York City, www.bettycuninghamgallery.com.

More of Emil Nolde! Click here if you are unable to view the video.

3 Famous Beds in Art

The bed is our earliest memory and perhaps our last. It is a place of repose, a place of dreams, a place to share secrets and to hide them.

Artists throughout history have used the bed as a backdrop to drama, passion, and scenes of sheer beauty.

Olympia, 1863

Édouard Manet

Musée d'Orsay, Paris, France

Shocking at the time of its unveiling, Manet’s Olympia wasn’t the picture-perfect French woman that some would have expected to see on a bed. Instead, she was a courtesan. The focus of public attack when it was first hung in the Salon of Paris in 1885, this famous work depicts the model not as the accustomed idealized, mythological female, but as a real woman with her flaws and all…something totally unacceptable to the French art critics.

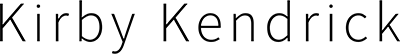

Vincent van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles, 1889

Vincent van Gogh

Chicago Institute of Art

The bright colors and rolling shapes of van Gogh’s bedroom in the Yellow House in France have at their emotional heart his bed. It is the bed of an ascetic, a lonely man, a dreamer revisited by unfulfilled dreams. This empty bed contains van Gogh’s troubled soul.

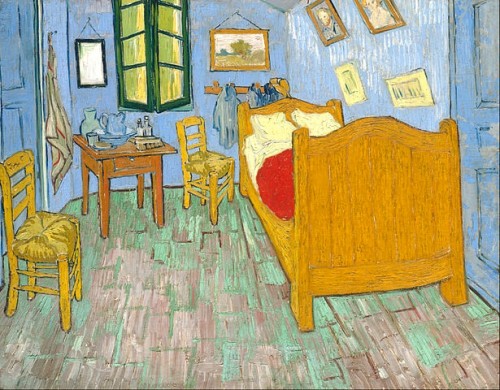

Bed-In for Peace, Amsterdam, 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono

Performance Art

Knowing that their wedding would cause a huge stir in the press, John Lennon and Yoko Ono decided to use their honeymoon to help champion world peace. On March 25, 1969, five days after their wedding, the duo climbed into the bed of room 902 at the Amsterdam Hilton and invited the media.

The couple’s interviews were reported in newspapers, radio, television, and newsreels worldwide. They received hostility, bemusement and mirth from the rest of the world, but their peace message was nonetheless widely distributed.

The mystery of Manet’s Olympia! Click here if you are unable to view the video.

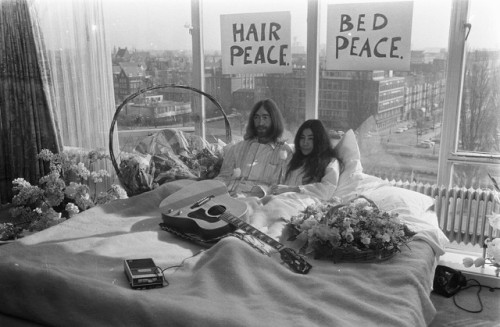

Lady in Gold

Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I, 1907

Gustav Klimt

Neue Galerie, New York City

The young woman floats in a shimmering crust of gold. Her dark head emerges, as if drowning in gold. Her look is sultry, an earthly goddess.

The model, Adele Bloch-Bauer, was 26, Jewish and the wife of a wealthy sugar baron in Vienna. The painter was Gustav Klimt, the most celebrated artist in Austria. The year was 1907.

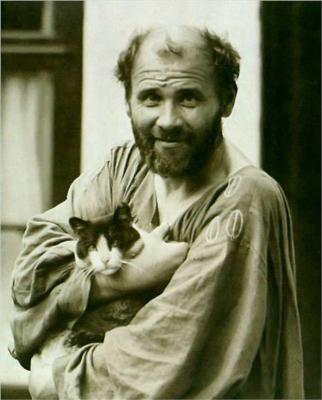

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918)

Gustav Klimt was the son of an impoverished gold engraver. So poor was he as a boy, that he missed school for a year because he didn’t have the correct trousers to wear. But he learned about gold, and in the Vienna of the early 1900’s, gold symbolized power. Gold leaf adorned statues, uniforms, palatial estates…and Klimt’s paintings.

Klimt’s Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I is his most acclaimed work.

Adele Bloch-Bauer died of meningitis in 1925.

Death and Life, 1916

Gustav Klimt

Leopold Museum, Austria

In 1938 Hitler and Goebbels imposed crushing and murderous restrictions on the Jews of Vienna. Their art was the first to be plundered.

Adele Bloch-Bauer’s widowed husband, Ferdinand Bauer, was stripped by the Nazis of his sugar refineries, his palatial home and his art…including the brilliant Klimt painting of his wife, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I.

The remarkable painting was hung in the Belvedere, the Austrian palace museum in Vienna. There was a problem, however. The title of Klimt’s painting had a Jewish name. Under Nazi regime no painting hanging in an Austrian museum could have a Jewish name.

The Nazi solution: the name was changed to The Lady in Gold.

The rightful owner of the glorious work, Ferdinand Bauer, escaped to Switzerland and died in poverty in 1945.

Sixty-eight years later, and after a protracted legal battle between the Austrian government and the heirs of Adele and Ferdinand, the portrait was returned to the family.

The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I now hangs at the Neue Galerie in New York City. Cosmetics giant Ronald Lauder bought the painting from the heirs in 2006 for $135 million.

Watch this “Women in Gold” movie trailer starring Helen Mirren and Ryan Reynolds.

Click here if you are unable to view the video.

See this terrific discussion on Klimt’s paintings.

Click here if you are unable to view the video.

Kandinsky and Münter Love Affair

Self-Portrait in Front of an Easel, 1909

Gabriele Münter

Princeton University Art Museum

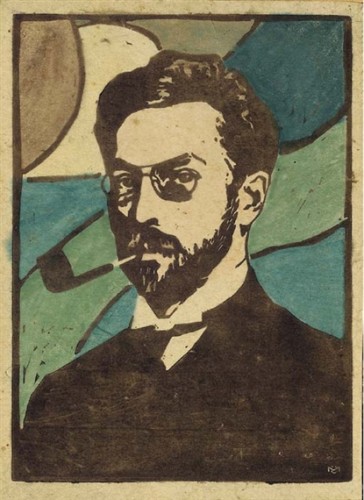

Portrait of Wassily Kandinsky, 1906

Gabriele Münter

Munich Municipal Museum

He was 36, her art teacher, and a dashing provocateur of the strict German art establishment in 1902.

She was 25, a liberated woman and one of the few females who dared to be an artist.

Together with a select group of Germans and Russians, they founded the rebellious cadre of artists known as “Blue Rider.” This group of maverick artists began the Expressionist movement in Germany.

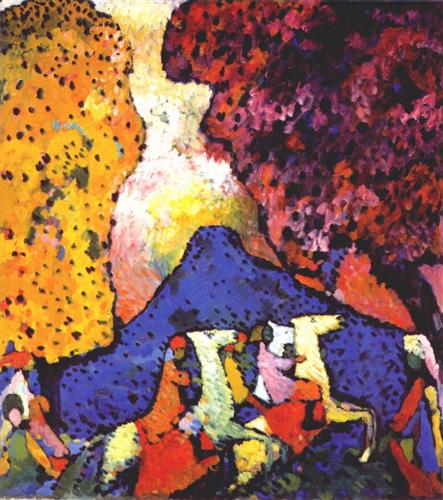

Blue Mountain, 1908-1909

Wassily Kandinsky

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Vassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter, teacher and student, began a passionate love affair.

Obstacle: Kandinsky was married, his estranged wife in Russia. After he promised to divorce his wife and marry Münter, the couple lived and worked together for 10 years, bringing out the highest creativity in each other.

Kandinsky’s Russian divorce was not granted.

WWI began. Kandinsky was compelled to return to Russia. Münter, remaining in Germany, promised to safeguard hundreds of his and other “Blue Rider” paintings in their house near Munich until he returned.

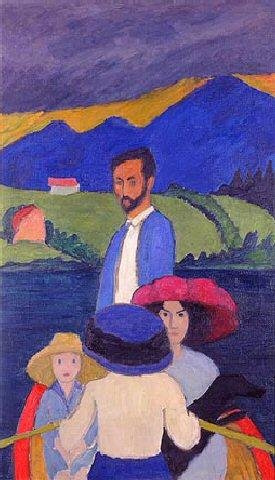

Boating, 1910

Gabriele Münter

Milwaukee Art Museum

Kandinsky finally obtained a divorce in Moscow. Without telling Münter, at 51 years of age he married a 24-year-old woman named Nina. Münter, upon discovering the secret marriage, refused to return Kandinsky’s paintings. He never saw these paintings again.

Abandoned she may have felt, but Gabriele Münter kept her promise! For 30 years she sheltered Kandinsky’s work.

In the dark years of fascism, when Hitler outlawed “degenerate” art, Münter hid the paintings in the basement of her house. In spite of several house searches by the Nazis, the cache of art was not discovered.

After the war, Münter once again kept the paintings hidden. This time from the Russians, who were “expatriating” art for The Hermitage, their state museum.

On her 80th birthday, in 1957, Gabriele Münter gave the art world her greatest gift. She donated the incredible treasure trove of over 1,000 “Blue Rider” works to the Munich Municipal Museum.

Gabriele Münter is considered the savior of early German Expressionism.

Blue Rider: Rebel Art

Winter Landscape I, 1909

Wassily Kandinsky

A little over 100 years ago, in 1911, a group of Russian and German artists working in Munich rebelled against the established traditions of art in Germany. The group named themselves “Blue Rider.”

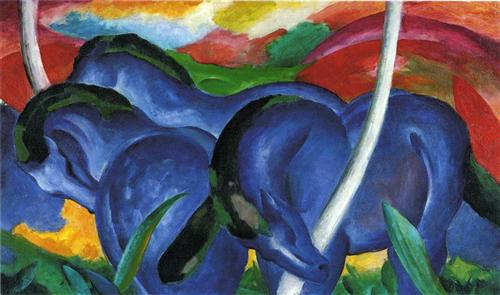

The Large Blue Horses, 1911

Franz Marc

The name was born in a conversation between two of the founders, Franz Marc and Wassily Kandinsky. Kandinsky felt the color blue was spiritual and Marc believed animals had more of this spiritual connection in the natural world than humans…hence, Blue Rider.

Study for Composition VII, 1913

Wassily Kandinsky

Blue Riders felt colors should be in harmony and resonate like music.

Art historian and author Cornelia Feye notes that Kandinsky was a “synaesthesist,” meaning that he could hear colors and see sound. After hearing a performance of Wagner’s opera Lohengrin in Moscow he said:

“I saw all my colors in spirit, before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.”

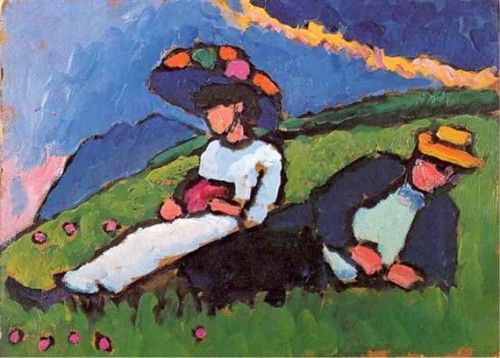

Jawlensky and Werefkin, 1908

Gabriele Münter

Gabriele Münter, also one of the founders of Blue Rider, collected children’s art. Although classically trained, she used simplified forms and colors expressing child-like innocence in her paintings.

A passionate but devastating 12-year love affair developed between Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky…another story…stay tuned for the next blog post!

Blue Rider was disbanded with the onset of WWI and the tragic war death of Franz Marc. The small avant-garde group is considered to be fundamental to the German Expressionist movement.

See Kandinsky’s greatest paintings. Click here if you are unable to view the video.

More about Cornelia Feye, art historian and author, www.CorneliaFeye.wordpress.com.